The Procession by Paul Moore

Part III - A Meditation

Paul Moore is certainly among the greatest sculptors of his generation, not only with collectors and admirers of American Western art, but anywhere, including numerous commissions for portraits of his contemporaries, public monuments, including the colossal Oklahoma Centennial Land Run Monument in Oklahoma City, a 365 foot epic consisting of 45 human figures and numerous horses and wagons--all life sized, to smaller compositions many of which depict scrupulously researched Native Americans of many different tribes. In addition, he is a Professor of Sculpture at the University of Oklahoma and has passed his craft down to his sons. He is also a prolific collector of objects and artifacts and has a profound knowledge of the history of American sculpture. There are two full-length interviews, one produced by the National Sculpture Society (2021) and the other (2017) in the Gallery of America series produced by PBS. A grand selection of his varied works is available to see on his own website Crown Arts, Inc. I give you links to all three below. So much has been written and videotaped about him and his body of work by so many who know him, that I urge anyone who is interested to seek expert information from the abovementioned sources.

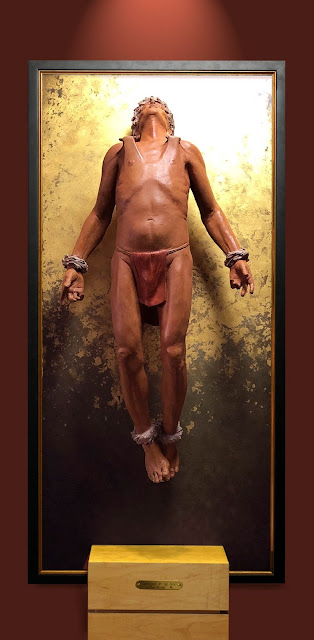

Here, I write only about two small pieces. I have never met Paul Moore, and my only direct experience of his work is The Procession, now in the collection of the Briscoe Museum, which was in the 2020 Night of ArtistsShow and a James Bowie Sculpture prize that year, (this work had also won the prestigious Prix de West the previous year), and another of his works Suspension To The Sun which was featured in the 2021 Night of Artists; I include a photo of it here with some trepidation since I do not know where it is now and who holds the copyright for the reproduction (I hope I will be forgiven).

Paul Moore - Suspension to the Sun

Both these works were done around the same period, during the time of Covid, and are part of a group of mixed media pieces that examine the fusion of Native American with Christian beliefs. Some are like altarpieces, and unlike The Profession, these images are confined to their European Gothic frames (except for a Bison head that rides outwards like a cuckoo clock when its doors are opened). Suspension to the Sunshows a single figure centered in front of a plain rectangular frame. The figure is suspended above the ground by means of ropes (here invisible) tied to wooden pegs that pierce his shoulder muscles.

The inspiration for this, as Moore explains on his website, is the Mandan ceremony, called the O-Kee-pa, held in spring when young men of the tribe endured an initiation ceremony that lasted four days. Part of it consisted of the young men having similar piercing of their shoulder and back muscles as well as by darts and suspended from the ceiling of the Mandan Medicine

|

| George Catlin - Okee-pa Ceremony: The Cutting |

Lodge by ropes. This was only the beginning, for the suspension was not to kill, but an ordeal to achieve visions in a state of trance. They then went through other ordeals. George Catlin had been present at the ceremony in 1832 and recorded four episodes from it with broad brushstrokes. Catlin's rapidly-painted initiates look slender and ragged, and they are seen from the distance within the lodge.

Moore presents the man, but in a very different way. The figure is presented frontally, his pierced shoulder muscles looking almost like straps. His spread-out arms and hand gestures suggest endurance, and also part of his self-offering. For Catholics, the frontal suspended figure, including the slightly joined feet, may evoke Jesus on the Cross, but his head, tilted backwards to the light, implies an ecstatic experience emphasized by the gold leaf behind him that reflects the studio lighting above it. The closest thing I can think of is Caravaggio's Conversion of St. Paul, but that light-encompassing figure lies foreshortened away from the

.jpg) |

| Caravaggio -St. Paul |

viewer on the ground, and he's struck blind by his vision. And the heroic nature of Moore's young man with a rope crown, which from the viewer's angle resembles a laurel wreath, tilts towards, and receives the light--an ecstatic vision that climaxes his ordeal. It's a depiction of the crowning moment of a vision quest, part of an age-old and universal initiation. This is a living hero--but all the muscular tension makes it hard to contemplate for long.

This work has a similar spiritual power to The Procession, but the effect on the viewer is different. I as a viewer can receive a powerful spiritual jolt from Suspension, but its upward-gazing intensity can only inspire the onlooker for a short time, and we can never share it. The wooden block, placed in front of the picture with its label, is also a distancing mechanism. The viewer is not invited to participate in this ritual, but to experience it in their own inner thoughts. The Procession is just the opposite: it appears to move towards you, soon you will be embraced by its spirituality--drawing you in.

___________________________________________

Paul Moore's Suspension in the Sun can be seen on his website: https://crownartsinc.com/art-gallery/ols/products/xn-suspension-to-the-sun-ol9lnb

Others in this same series can be accessed at the same website; click on the years 2019 and 2020.

George Catlin's Okee-pa scenes (1832) consist of four paintings. Three are in the Anschutz Western Art Museum, Denver. The fourth ("The Cutting Scene") is in the Denver Art Museum https://www.denverartmuseum.org/en/edu/object/cutting-scene-mandan-o-kee-pa-ceremony. These scenes were reissued under Catlin's supervision as lithographs, starting in 1841, and he lectured on them too. See also George Catlin and His Indian Gallery, Washington, Smithsonian Institution, 2002, pp. 48, 210-215.

,_Sevilla,_Holy_Week._Penitents_-_A1809_-_Hispanic_Society_of_America.jpg)